Pollination, fertilisation and fruit-set

Updated November 2023 to include results from 2022 season

High quality flowers on the female parent variety should be pollinated at the optimal time and under suitable environmental conditions. The likelihood of achieving success is increased by pollinating more than one (emasculated) flower per cluster.

Flower selection and quality

Detailed guidance on how to increase flower quality and pollination rates in commercial apple orchards can be found in the ‘Apple Best Practice Guide’. Much of this is relevant to improving the success of hand pollination when making crosses.

- Flowers formed on spurs are generally of higher quality than those on axillary shoots.

- Flowers on spurs growing on two- or three-year-old wood often produce better quality flowers than spurs formed on older wood.

- Flowers are initiated during the previous summer, and those on axillary shoots are initiated much later than flowers on spurs and short terminals. Consequently, they are less developed at the onset of dormancy in the late autumn, and are usually of poorer quality in the next spring.

- Flower bud quality is usually improved by light, as opposed to severe, winter pruning. Summer pruning can improve flower bud quality on spurs by removing shading.

- The first flowers to open on a variety are often those with the best setting and fruit growth potential.

Flower selection to avoid frost damage

In many apple growing regions frost damage is a major cause of failed pollination, fertilisation and fruit set. Less than an hour of air temperatures a few degrees below freezing can produce severe and irreversible effects. An effective way of hedging against the unpredictability of frost damage in a crossing programme is to use parental varieties flowering at different times during the spring. Hand pollinating over several weeks should increase the chances of some crosses escaping frost damage.

The sequential opening of flowers on an individual tree can also be exploited. This sequence is the tree’s way of compensating for failure to set fruit due to frost damage. As described by Dan Neuteboom, the earliest and best quality flowers are formed on two-year old wood and young spurs. Flowers forming on three-year old wood are smaller and open a little later. The latest and smallest flowers open 7-10 day later on one-year-old wood. These flowers together with those on three-year old wood may abort naturally in years when the earlier flowers set well. However, they provide a second or third chance to set fruit in years of damaging frosts. It follows that to increase the chance of making a successful cross it is worth hand pollinating flowers on both one and two year old wood on a tree used as a female parent; this may require two visits, separated by up to 14 days.

Effective Pollination Period (EPP)

The EPP is a commonly used measurement of ‘flower quality’, defined as the number of days after the flower opens during which it can receive pollen and still set fruit. This period covers the time taken for the pollen to germinate, the pollen tube to grow and the time during which the ovule remains viable. EPPs are determined by measuring the success rates of pollinating flowers on the day they open and on each of the subsequent days. According to the ‘Apple Best Practice Guide’:

- Good quality apple flowers should have EPPs of 3-5 five days under orchard conditions in the UK.

- Flowers only able to set fruits when pollinated on the day of opening have low EPPs and are classed as poor quality.

- Spur or terminal flowers usually have longer EPPs than those formed as axillaries on one-year-old wood. The short EPPs of the latter are probably due to their shortened flower development. The risk of poor fruit set on axillary flowers is therefore higher than on spur or terminal flowers.

- EPPs differ between varieties, and also vary from year to year.

The factors controlling EPPs are not fully understood but the ‘Apple Best Practice Guide’ advises that adopting best practice will induce stronger flowers, more viable pollen, better pollination conditions and a higher success rate at fertilisation.

Optimal time of pollination

If you don’t know the EPPs of a variety, the default action is to pollinate flowers on the day, or day after, they open. According to MAFF (1973), recently opened flowers (i.e. one or two days from opening) ‘if pollinated by good compatible pollen, are likely to be more effective than older flowers in giving a reliable set of fruit’. Similarly, the ‘Apple Best Practice Guide’ states that highest pollination rates are usually achieved on the day the flowers open.

The condition of the stigma is often mentioned when discussing pollination. The best time to pollinate is traditionally considered to be when the surface of the stigma is ‘sticky’. Summarising from the ‘Apple Best Practice Guide’, the surface of the stigma consists of tiny papillae. These are turgid when the flower first opens (anthesis) and a surface secretion develops (stickiness). At this point the flower is considered to be receptive to pollen. The papillae dry out and collapse within two days. However, pollen has been shown to germinate on stigmas as late as ten days after flower opening (Braun and Stösser, 1985). This suggests that ‘stickiness’ is not a prerequisite for successful pollination and fertilization. However, in general it is likely that the longer hand pollination is delayed once a flower is opened the lower the likelihood of success.

Optimal conditions for fertilisation

The process of fertilisation comprises germination of the pollen grain on the stigma, the growth of the pollen tube down the style, its union with the ovule, and the subsequent fertilisation of the egg (♀) by one of the two sperm nuclei (♂) to form the embryo.The other sperm nucleus unites with the two polar nuclei in the ovule to form the triploid endosperm tissue. The embryo and endosperm both develop within the seed (pip). The fleshy, edible part of the developing fruit is actually the swelling of maternal ovary and receptable tissue. It is worth noting that this part only contains and expresses genes from the maternal parent.

The whole fertilisation process takes up to 10 days; two to four days for the pollen to germinate and the pollen tube to reach the base of the style, followed by six to eight days to cross the pericarp and unite with the ovule. Poor fruit set resulting from short EPPs is thought to be related to ovule longevity and growth of the pollen tube down the style, rather than to pollen germination itself.

Environmental conditions have a large impact on fertilisation. Pollen grains need to take up water (hydrate) in order to germinate. Hence, drying winds at the time of pollination will reduce their viability. However, pollen also loses viability if completely wetted, so rain will significantly reduce germination rates. Germination is also temperature dependent, with optimum temperatures of 15 - 25ºC, although pollen from some varieties can germinate and grow at much lower temperatures. The growth rate of the pollen tube is almost entirely dependent on temperature; if the tube does not grow down the style within 2-4 days fertilisation may not occur.

Levels of fruit-set and seed-set

An apple flower has five stigmas. Each stigma is connected via the stye to a carpel, each of which contains two ovules. It is not normally necessary for all ten ovules to be fertilized and produce seed for satisfactory fruit development, and with some varieties very few seeds appear to be necessary. However, many varieties develop misshapen fruit unless most of the cells of the core contain at least one fully developed seed (MAFF, 1972).

Surprisingly, we haven’t come across many figures for the success rate of hand pollination in terms of fruit-set. Trials with the variety Discovery at Long Ashton Research Station (Stott et al.,1973) showed that 9% of flowers set fruits if pollinated on the day of opening but only 1% set fruits when pollinated two days after opening. In a large scale trial (Brittain,1933) with Cox’s Orange Pippin, Golden Russet and Northern Spy, selfing produced a mean fruit set 1.5%, compared with 7% when cross-pollinated. Keulemans et al. (1994) hand pollinated 1, 3 or 5 stigmas per flower, and either 1 or 3 flowers per cluster. They harvested the resulting fruits when ripe and found that seed set increased with the number of pollinated stigmas on the flower, from 0.48 to 1.38 seeds per pollinated flower. Final fruit-set expressed as a percentage of flowers pollinated also increased from 24% to 39% with increasing numbers of pollinated stigmas.

The effects of pollinating 1 or 3 flowers per cluster were mixed. There was little effect on initial fruit set before the ‘June drop’. However, June drop increased from 5% (1 flower) to 21% (3 flowers). Consequently, final fruit-set decreased from 38% (1 flower) to 26% (3 flowers). On the other hand the average number of seeds/fruit harvested was 2.6 (1 flower) and 2.8 (3 flowers). Interestingly they also observed that the germination of seeds harvested from the fruit was negatively correlated with seed number, probably due to competition between seeds in the fruit.

At face value the results of Keulemans et al. (1994) call into question our practice of pollinating three flowers per cluster, in that a lower proportion of the pollinated flowers set fruit. However, our approach increases the chances of at least one of the three flowers on the cluster being in optimal condition when we pollinate the cluster. This should increase the chance of at least one set fruit from a particular cross. Logistically, we also find it quicker and easier to prepare, protect and hand pollinate three flowers per cluster, compared with one flower on each of three different clusters.

Success rates at Ystwyth Valley Apple Breeders

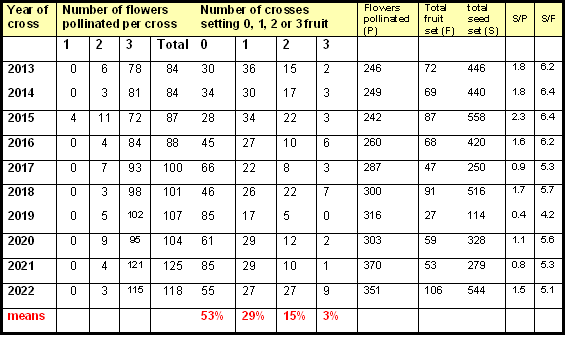

Fruit-set from crosses made at YV Apple Breeders each year between 2013 and 2022 is shown in the table opposite. 'Fruit-set' is defined here as the number of apples harvested at maturity. Total 'seed-set' is the number of seeds extracted from harvested apples. Each cross usually comprises pollination of three flowers on a single cluster, although in a few cases less than three flowers are pollinated. The values in this table are based on the pooled results of crosses made between many different varieties each year, but include only ‘defined’ (both parents known) as opposed to ‘open’ (only female parent known) crosses. They show:

- The number of crosses producing one or more fruit at harvest time, expressed as a percentage of the total number of crosses made, were: 2013 (63%), 2014 (60%), 2015 (68%), 2016 (49%), 2017 (33%), 2018 (54%), 2019 (21%), 2020 (41%), 2021 (32%) and 2022 (54%), giving an average of 48% across the ten years.

- Averaged over the ten years, 53% of crosses failed to produce any fruit, 29% produced one fruit, 15% produced two fruit, and only 3% produced three fruit.

- Final fruit-set expressed as a percentage of the number of flowers pollinated was: 2013 (29%), 2014 (28%), 2015 (36%), 2016 (26%), 2017 (16%), 2018 (30%), 2019 (9%), 2020 (19%), 2021 (14%) and 2022 (30%), giving an average of 24% across the nine years. These values compare with the final fruit-sets of 38% (1 flower) and 26% (3 flowers) reported by Keulemans et al. (1994).

- The average number of seeds (pips) per fruit harvested over the ten years was 5.6. The value expressed on the basis of the total number of flowers pollinated was 1.4 seeds/pollinated flower. This compares with the 1.38 seeds per pollinated flower reported by Keulemans et al. (1994) when all five stigmas on a single flower were pollinated.

The wide variation in the results between years makes it difficult to accurately estimate the number of crosses required to produce a desired number of seeds. The high failure rates for crosses made in 2017 (66%) and 2019 (79%) were mainly caused by low temperatures and frost damage to the flowers following pollination.

Effects of parental variety on success rates at YV Apple Breeders

Crossing success rates vary widely with apple variety, and in some cases also depends on whether the variety is used as male or female parent. We are compiling a data-set on varietal differences, scoring each cross (3 flowers pollinated) as ‘successful’ if at least one fruit survives to final harvest. ‘Failures’ are classed as either ‘failed pollination’, where no fruit is set from the outset, or ‘failed post-pollination,’ where any remaining fruit are lost during or after the June drop. This data-set is updated annually with the results from the current year's crosses.

The average success rates across all varieties used in five or more crosses between 2010 and 2022 are 44%, when used as the female parent, and 51%, when used as the male parent.

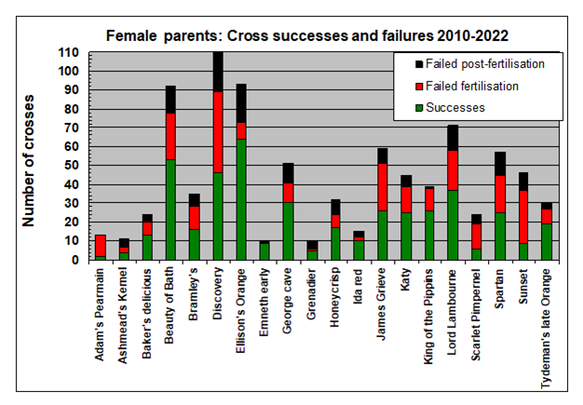

Success rates among a sample of 20 varieties used as female parents in 873 crosses between 2010 and 2022 are compared in the figure below.

- Most diploid varieties have success rates >50% when used as female parents.

- Reliable female parents include Beauty of Bath, Ellison's Orange, Lord Lambourne and King of the Pippins.

- Of the 425 failed crosses in this sample of 873 crosses, the majority of failures were associated with fertilisation (64%) rather than later losses during June drop and nearer harvest (36%) .

- Proven triploid (or aneuploid) varieties (e.g. Adam’s Pearmain, Annie Elizabeth. Ashmead’s Kernel) have low success rates as female parents, associated with failed pollination or fertilisation.

- Sunset and Scarlet Pimpernel have relatively low success rates for diploids, mainly associated with failed pollination or fertilisation.

Success rates among a sample of 20 varieties used as male parents in 700 crosses made between 2010 and 2022, of which 356 were successful, are shown in the figure below.

- The majority of varieties have success rates >50% when used as male parents.

- Reliable male parents include Katy, King of Pippins and Honeycrisp.

- Some triploid (or aneuploid) varieties like Adam’s Pearmain have relatively high success rates as male parents, whilst others like Annie Elizabeth have poor success rates.

Beauty of Bath is a good example of a variety with widely different success rates depending on whether it is used as the female (58%) or male (33%) parent. In

contrast, we find that Katy and Ellison's Orange have very similar success rates irrespective of whether they are female or male parents.

Year to year variation in success rates of different varieties used as female parents

Success rates of individual varieties used as female parents often vary widely from year to year. This variation is illustrated in the following graphs for three

varieties (Discovery, Beauty of Bath and Ellison's Orange) when used as female parents between 2011 and 2022.

Overall success rates between 2011-2022 decreased in the order Ellison’s Orange (70%) > Beauty of Bath (58%) > Discovery (42%). In most years the majority of failed crosses involving Ellison’s Orange were due to fruit drop following fertilisation, whilst those involving Beauty of Bath were associated with failed fertilisation. In 2017 most of the crosses made with Discovery and Beauty of Bath failed, at the fertilisation stage due to frost, whilst most of the crosses made with Ellison’s Orange were successful.

References

Braun J, and Stösser R. 1985. Narben- und Griffelstruktur ihr Einfluss auf Pollen keimung, -schlauchwachstum und Fruchtansatz beim Apfel. Angew. Bot. 59: 53-65.

Keulemans J, Eyssen R, and Colda G. 1994. Improvement of seed set and seed germination in apple. p. 225-228. In: H. Schmidt and M. Kellerhals (ads.). Progress in

temperate fruit breeding. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, Netherlands.

MAFF. 1972. Apples. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Bulletin 207.

HMSO, London. 205p.

MAFF. 1973. Flowering Periods of Tree and Bush Fruits. Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Technical Bulletin 26. HMSO, London. 76p.

Dan Neuteboom. Fruit Tree Growing. 2021 Suffolk Fruit and Trees – The Fruit Tree Specialists. https://realenglishfruit.co.uk/

Stott KG, Jefferies CJ, and Jago C. 1973. Pollination and fruit set of the apple Discovery. Report of Long Ashton Research Station for 1972, 31.